Introduction

Origins and Early History

Travelling Communities during the 20th Century

Groups Campaigning for Travellers' Rights

Traveller Ethnicity and Culture

Sound Clips - coming soon

Introduction

Migration is an inherent part of a way of life that has existed in many cultures for hundreds of years. For travelling communities this way of life has involved following the patterns of nature and living with a sense of freedom and flux on the road. It is also a way of life that has brought with it the status of being 'outsiders' living on the margins of society and the experience of discrimination. From Romany gypsies and Irish travellers to fairground people and water gypsies, travelling communities are varied and distinct with their own cultural traditions, language and ethnicity. Despite their differences they are all united by a desire to tread their inherited paths and to pursue a way of life that challenges the conventions and stereotypes held by wider society.

<return to top>

Origins and Early History

Gypsies are thought to have originally migrated from India at the end of the first millennium towards the west, passing through Egypt, Russia, Romania (where they adopted the name Romany) and Turkey before arriving in Europe. Whilst some look to India, others have traced their mythical origins to stories in the Bible such as that of Abraham's maidservant who was driven away but gave birth to a great tribe [MS 4000 2/97/1/2/2 p52]. The word 'gypsy' is an abbreviation of 'Egyptian' which was applied to the Romany people in the Middle Ages since it was thought that they originated in Egypt. Travellers survived by telling stories and fortunes, picking up other skills along the way such as an understanding of horsemanship, wood and metalworking, as well as music and dancing skills which were easily transportable (Rudge, 2003:6).

The early presence of gypsy travellers in Britain dates from the 16th century which was also the period in which their persecution and status as 'outlaws' started to develop. In 1530 the Egyptians Act was passed to both expel and halt the migration of "the outlandish people calling themselves Egyptians" and was the first piece of legislation to criminalise travelling communities. An amendment to this act in 1554 imposed a death sentence on any gypsies found in England. Over the centuries further legislation was passed, including the 1743 Justice Commitment Act, the Vagrancy Act 1824 and the Highway Act 1835 which not only set the scene for the legislation that was to follow in the 20th century, but also served to criminalise and negatively stereotype travellers in the popular imagination.

By the 18th century travellers had developed working trails in rural areas which over time became established routes for groups of gypsies. Routes were determined by the seasons and the availability of agricultural work, and during the winter the travellers settled temporarily in their base where they would arrange horse deals and bare-knuckle fights and create items for sale such as pegs, flowers and other trinkets (Rudge, 2003:9). Water gypsies would make a living by transporting goods especially coal along the canal networks which were developed in the 18th century.

<return to top>

Travelling Communities during the 20th Century

As Britain became industrialised and work increasingly mechanised particularly during the 20th century, there was a reduction in the need for seasonal labour; consequently many travellers exchanged the rural environment for an urban one where they engaged in work to suit the new landscape such as scrap dealing, tree felling, car dealing and tarmac laying. However despite their ability to adapt to new environments, the modern age brought the sedentary and travelling communities increasingly into conflict.

The development of land, in response to the economic boom after the Second World War, meant that stopping places became scarce and travellers who moved to urban locations were confronted with additional barriers to their way of life including prejudice and hostility. Hundreds of Irish travellers, like many post-war migrants, had been attracted to England by the prospect of economic opportunity (Puxon, 1968) and the reception given to them was likewise far from welcoming. The lack of sympathy for their way of life expressed by council official and police combined with conflict over land use was the source of many struggles for travelling communities during the 1960s and 70s.

Many struggles were fought against the treatment of travellers by local authorities and centred on forced evictions from unauthorised sites. Official local authority sites for travellers were limited in number and catered for only a small percentage of travelling families. As a result many settled wherever they could find space, from roadside verges, woodland and quarries to rubbish tips and factory grounds where basic amenities such as a water supply and sanitation facilities were often hard to access. Families faced harassment from local authorities which, along with the police, enforced the letter of the law, moving them on from region to region. It was not uncommon for their welfare to suffer. A gypsy traveller interviewed for the radio programme 'The Travelling People' in 1963 describes how the unsympathetic attitude of the authorities led to her child being born on the road:

"I was expecting one of my children, one of my babies, and my son ran for the midwife. In the time he was going after the midwife, the policeman come along. "Come on," he says, "Get a move on. Don't want you here on my beat." So my husband says, "Look sir, let me stay, my wife is going to have a baby." "No, it don't matter about that," he says, "You get off." They made my husband move and my baby… was born on the crossroads in my caravan. The horse was in harness and the policeman was following along behind, you know, drumming us off… born on the crossroads." [MS 4000 2/97/1/2/2 p29]

In 1963 the outrage of Sparkbrook residents at the living conditions and behaviour of Irish travellers in a number of multi-occupied properties in Grantham Road attracted local and national media attention. Alderman Harry Watton, Chairman of the General Purposes Committee of the City Council led a campaign to remove the travellers which included an application to compulsorily purchase fourteen properties. The travellers were viewed as having no place in the city despite their long history in Birmingham:

"I think you are endeavouring to defend something that is historically outdated: the tinker and the wanderer. There may be places for them in some parts of the world, but there isn't in an industrialised urban community." [MS 4000 2/97/1/2/2 p57]

The authority's attitude, echoed by local newspapers, dehumanised the travellers, presenting them as parasites invading the local community. One headline described them as "human scrap vultures" swarming in for "slum drive pickings" (Birmingham Mail, 9/7/1963).

It was gradually brought to the attention of the council that a long-term solution to the 'problem' of travelling communities could not be solved by displacing them but would involve the provision of more authorised sites for them to settle on.

<return to top>

Groups Campaigning for Travellers' Rights

In the Midlands positive work was being done to assert the human rights of travellers. Like the migrants from the Commonwealth, travelling communities faced racial discrimination and were refused entry to shops, clubs and public houses. 'No Gypsies' signs could be seen outside pubs and during local elections in 1970 conurbation action groups in the Midlands circulated leaflets which incited racial hatred against Irish travellers (Kenrick and Bakewell, 1990:26).

The West Midlands Gypsy Liaison Group (WMGLG) was established in September 1969 as a result of a large-scale eviction in Balsall Heath in 1968, with the aim of increasing understanding among the settled, house-dwelling population of the life-style, problems and aspirations of gypsies. It was also involved in campaigning for the provision of permanent sites under the 1968 Caravan Sites Act. The Chairman of the group was Charles Parker and Vice-Chair was film-maker Philip Donnellan, director of the 1964 television documentary The Colony. From 1970-72 the WMGLG joined the Gypsy Council in supporting travellers in their conflict with Local Authority security officers and against local residents' Action Groups and the National Front which opposed unauthorised gypsy camping sites in Walsall. Importantly, the Liaison Group recognised that the treatment of gypsies was closely linked, especially in the West Midlands, with the treatment of other minorities [MS 4000/1/8/19 reports file: Report by the West Midlands Gypsy Liaison Group, February 1973].

The papers of the West Midlands Gypsy Liaison Group refer to a number of other regional and national organisations that were advocating gypsy and traveller rights during the 1960s and 70s some of which it had links with. These included:

- Walsall Committee for Human Rights

- The Gypsy Council

- National Council for Civil Liberties

- National Gypsy Education Council (Temeski Kris Te Romengo Jinapen)

- Gypsy Liaison Committee.

<return to top>

Traveller Ethnicity and Culture

"If ye's brought up to be a gypsy, you gotta be a gypsy. It's into your blood, isn't it? And if it's not in your blood, if you're not brought up to it, you can't BE one…It's what's into you's be a gypsy, what's into your bones, gotta be a gypsy." [MS 4000 2/97/1/2/2 p46]

Aspects of the distinctive cultures of travellers are revealed in the sound recordings made by Charles Parker for the 1964 documentary 'The Travelling people.' Interviews with travellers from Blairgowrie, Hemel Hempsted, Poole and Bishops Frume in Wales reflect the vibrancy of the oral tradition upon which the culture of travelling communities is built. Riddles, stories, love songs and murder ballads provide a taste of the freedom and hardship of the travelling life. To listen to some of these recordings, click on the links below.

<return to top>

Sound Clips - coming soon

<return to top>

Author: Sarah Dar

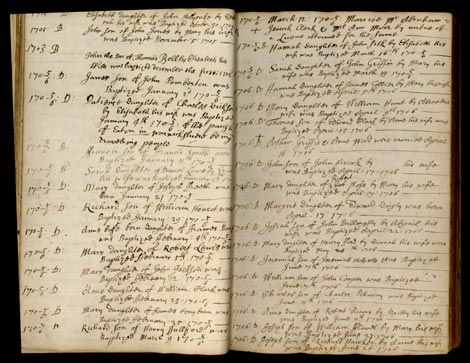

Main Image: Baptism register of St John's, Deritend [City Archives: EP 1/2/1/1]

<return to top>

|